Distributed systems design patterns are the established, reusable solutions to the messy, real world problems you hit when an application grows beyond a single machine. Think of them less as abstract theory and more as battle tested blueprints for building systems that can handle scale and chaos without falling over.

When Your Monolith Starts to Groan

We have all been there. It starts with small things. An API endpoint that is a few hundred milliseconds too slow. A database table lock that freezes up a key user workflow.

Then comes that pit in your stomach feeling during a product launch. You are watching the monitoring dashboard, praying the whole thing does not collapse like a house of cards under the traffic spike. I have restarted enough servers at 3 AM to know that feeling well.

This is the classic story of a monolith groaning under its own weight. What started as a clean, simple codebase has become a tangled mess. Deployments are terrifying, all or nothing affairs. A bug in the user profile module can suddenly take down payment processing. Onboarding a new engineer feels like handing them a map to a labyrinth with no exit.

The Inevitable Tipping Point

The jump to a distributed architecture is almost never a casual choice. It is a move forced on you by the pressures of success:

- User Growth: Your user base is exploding, and you simply cannot throw more RAM and CPU at a single server fast enough.

- Availability Demands: You cannot afford downtime anymore. The system has to be online 24/7, even when individual components fail.

- Team Velocity: Your dev teams are constantly stepping on each other's toes. The monolith has created a development gridlock, slowing innovation to a crawl. If this sounds painfully familiar, our guide on microservices architecture best practices might offer some relief.

This is not a new problem. The shift was pioneered by the early web giants wrestling with unprecedented scale. By 2010, services like Amazon were designing for hundreds of millions of users, which forced them to break things apart and replicate everything. Amazon's famous Dynamo paper, for instance, was born from the very real need to keep their ecommerce site running during the absolute chaos of Black Friday, processing millions of requests per minute.

The single biggest problem that distributed systems solve is how to coordinate independent services across an unreliable network where failure is not just a possibility—it is a certainty.

Getting your head around this one idea is the first major step. It changes the conversation from a vague "Should we use microservices?" to a much more practical "How do we build a system that can gracefully handle the inherent chaos of the real world?"

The design patterns we are about to dive into are the hard won answers to that very question.

Your Toolkit for Building Resilient Systems

So, you have finally admitted your monolith's days are numbered. The next question is usually a bit terrifying: "...What now?"

Diving into distributed systems can feel like sailing into uncharted waters. Without a map and a compass, you are going to get lost. The good news is that others have sailed these seas before and left behind a collection of powerful, battle tested tools. These are the fundamental distributed systems design patterns.

Think of them less like complex academic theories and more like practical blueprints for solving very specific, very real problems. Forget memorizing dry definitions; let us frame them with simple analogies. These are the first three tools you absolutely need to get your head around.

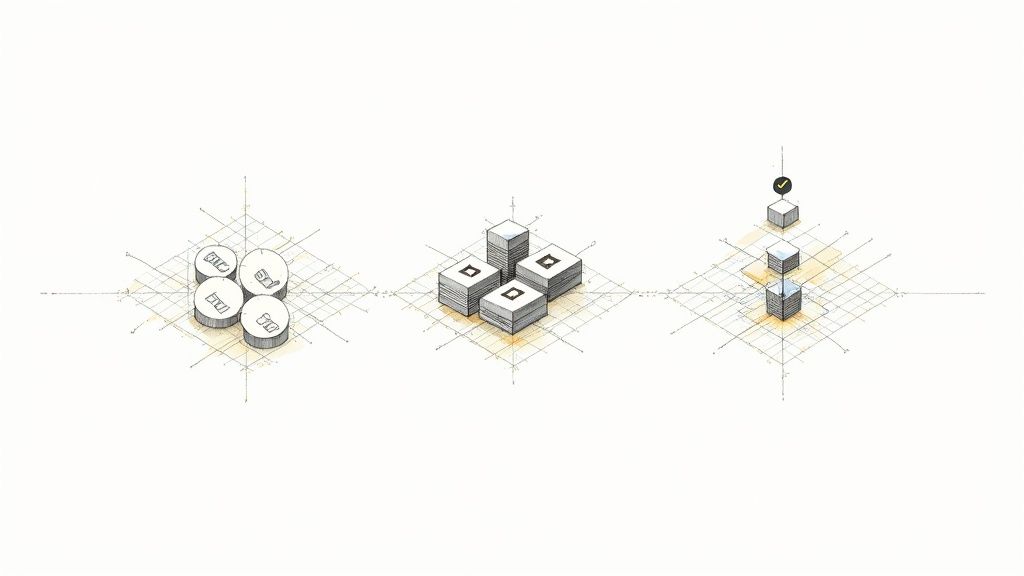

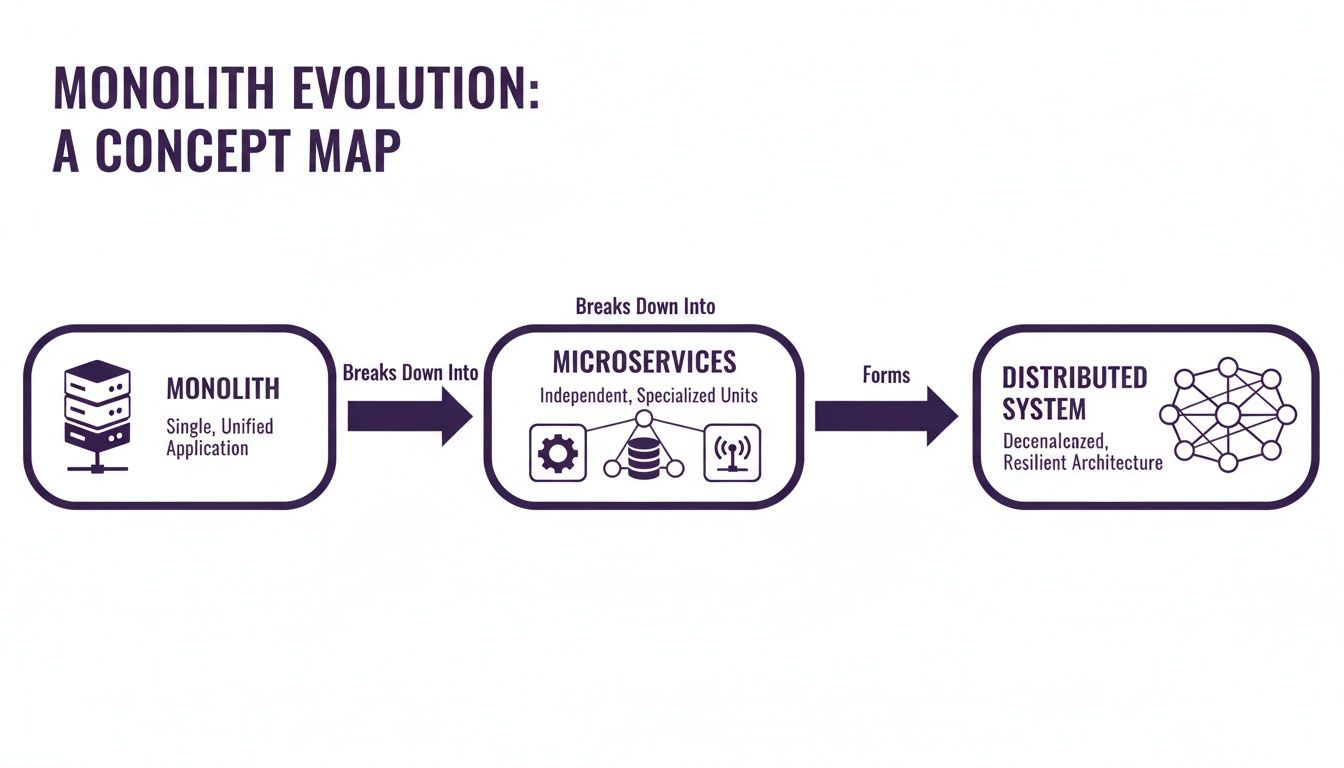

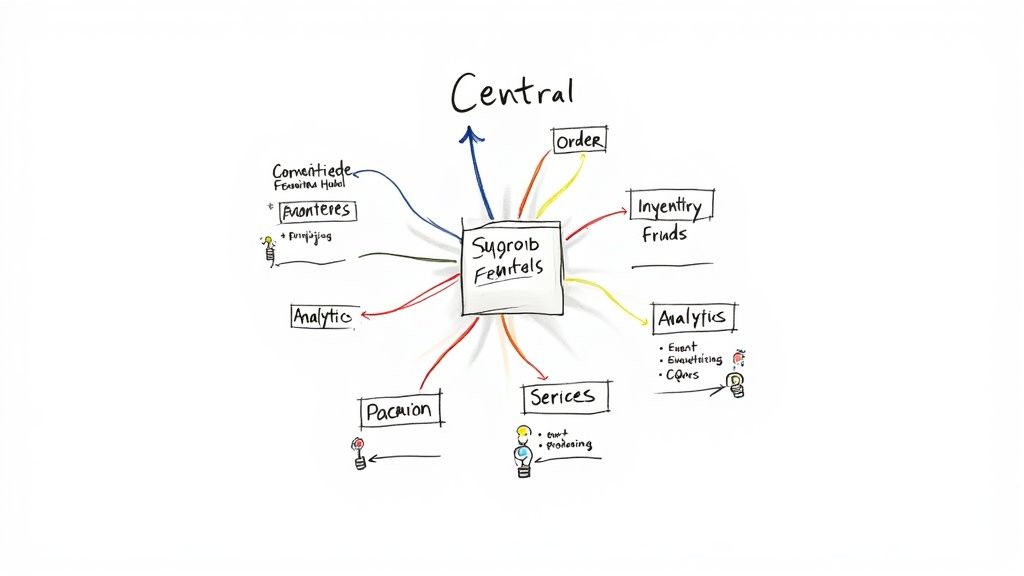

This diagram shows the typical journey from a single, monolithic app to a more complex—but far more scalable—distributed system.

As you can see, this evolution is not just for kicks. It is a direct response to the need for greater scale and resilience, moving away from a single point of failure toward a network of coordinated, independent parts.

Replication: Your Digital Safety Net

At its core, Replication is just about making copies of your data or services across multiple machines.

Imagine you have only one copy of a mission critical document. If it gets lost in a fire, you are in serious trouble. But if you have photocopies stored in different buildings, the loss of any single one is just an inconvenience.

That is precisely what replication does for your system. It is your first and best line of defense against hardware failure and the key to achieving high availability. When one server hosting your database goes dark, traffic can be instantly redirected to a replica without your users ever knowing anything went wrong. This pattern is foundational to nearly every resilient system you have ever used.

Sharding: How to Organize a Massive Library

Now, imagine your library has grown so huge that a single building cannot possibly hold all the books. What is the solution? You build new branches across the city and organize the books by genre—science fiction goes to one branch, history to another.

That, in a nutshell, is Sharding (also known as Partitioning).

It is the go to pattern for horizontally scaling your database. When a single database server chokes on the sheer volume of data or the number of queries, you split that data across multiple servers, or "shards." Each shard holds a distinct subset of the data, allowing your system to handle massive datasets and high throughput by spreading the load. No single server ever becomes a bottleneck.

Consensus: Getting Everyone to Agree

Finally, let us talk about Consensus. Picture a group of friends trying to decide which movie to watch. After some debate, they all have to agree on a single choice before anyone buys tickets.

In a distributed system, consensus algorithms are the formal process that allows a group of independent servers to agree on a specific value or state, even when some of them fail or network messages get lost.

This is absolutely crucial for tasks that demand bulletproof consistency, like electing a single "leader" from a group of servers or ensuring a financial transaction is committed correctly across multiple nodes. It is the pattern that brings order to potential chaos, guaranteeing that critical decisions are made reliably across the entire system.

Making the right architectural choice is always about understanding the tradeoffs. There is no single "best" pattern, only the most appropriate one for the problem at hand.

These are not just abstract concepts; they are measurable engineering choices. For instance, Google's Spanner chose to prioritize strong consistency for its transactional systems, accepting higher latency as the cost. In contrast, Amazon's Dynamo prioritized availability, accepting eventual consistency to ensure their ecommerce platform stayed online during peak traffic—a decision that has saved them from countless outages.

Choosing between these foundational patterns requires careful thought. As you implement them, keeping a close eye on your system's behavior with the right application performance monitoring tools becomes non negotiable.

Foundational Distributed Patterns Tradeoffs

Here is a quick cheat sheet to help frame your thinking.

| Pattern | Primary Goal | Key Benefit | Common Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Replication | High Availability & Durability | Survives the failure of individual nodes by having redundant copies. | Keeping all copies of the data synchronized (consistency). |

| Sharding | Scalability & Performance | Distributes data and load across multiple servers for massive scale. | Handling cross shard queries and rebalancing data as it grows. |

| Consensus | Consistency & Coordination | Ensures all nodes agree on a state, preventing data corruption. | Performance overhead; can be slow due to coordination needs. |

Each pattern solves a critical problem, but none is a silver bullet. The real skill is knowing which tool to pull out of the toolkit for the job at hand.

Designing for When Things Inevitably Break

In a monolith, a major failure is a crisis. In distributed systems, failure is just another Tuesday. The network will glitch, a downstream service will time out, and a deployment will go sideways. The most fundamental shift you can make as an engineer is to stop trying to prevent failure and start designing for it.

This is not about being a pessimist; it is about being a realist. The most robust systems are not the ones that never fail. They are the ones that gracefully handle failures without the user ever noticing. These systems are built on a foundation of fault tolerance, using specific patterns to contain the blast radius when something inevitably blows up.

Let us dive into the patterns that act as your system's emergency response team.

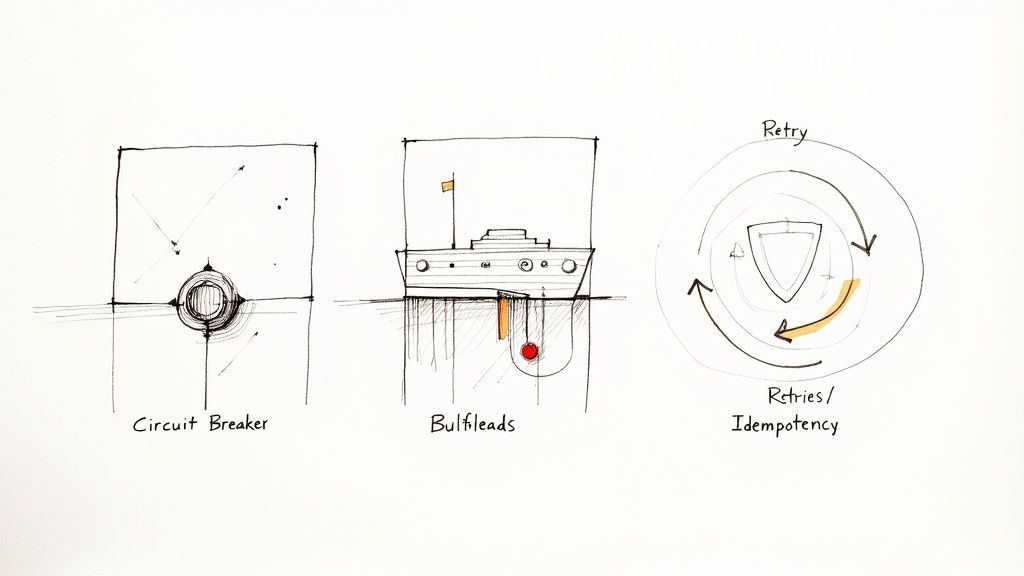

The Circuit Breaker Pattern

Think about the electrical panel in your house. When a faulty toaster starts drawing too much power, a circuit breaker trips. It cuts off electricity to that one circuit, preventing a fire that could take down the whole house. Critically, the rest of your lights stay on.

The Circuit Breaker pattern works the exact same way in a microservices architecture.

When one service—let us call it the PaymentService—repeatedly fails to respond, your calling service (the OrderService) should not just keep hammering it with requests. That only makes a bad situation worse, tying up its own resources and kicking off a dreaded cascading failure.

Instead, a circuit breaker wraps the call to the PaymentService. After a set number of failures, the breaker "trips" open. For a short time, any new calls to the failing service are immediately rejected without even trying to connect. This simple act gives the struggling PaymentService breathing room to recover. After a cooldown, the breaker might let a single "canary" request through. If it succeeds, the breaker closes, and normal operation resumes. If not, it stays open.

A Circuit Breaker protects your system from itself. It stops services from wasting resources on calls that are doomed to fail, preventing a localized problem from becoming a system wide outage.

This is not just theory; it is a critical survival mechanism. A core part of designing for failure involves comprehensive Disaster Recovery Planning to ensure your services can actually bounce back.

The Bulkhead Pattern

Let us stick with the heavy duty analogies. A large ship is divided into watertight compartments called bulkheads. If the hull is breached and one compartment floods, the bulkheads contain the water, preventing the entire ship from sinking.

The Bulkhead pattern applies this same isolation principle to your system's resources, like connection pools or thread pools.

Imagine your application has a single, shared thread pool for all incoming requests. Some requests are for a fast, reliable UserService, while others go to a slow, flaky third party ShippingAPI. If that ShippingAPI suddenly becomes unresponsive, all the threads in your pool will quickly get stuck waiting for it. Soon, no threads are left to handle requests for the perfectly healthy UserService, and your entire application grinds to a halt.

With the Bulkhead pattern, you would create separate, isolated thread pools for each service dependency.

- Pool A: 20 threads dedicated to the

UserService. - Pool B: 5 threads dedicated to the slow

ShippingAPI.

Now, if the ShippingAPI goes down, it can only ever exhaust the 5 threads in its dedicated pool. The other 20 threads are completely unaffected and can continue serving the UserService without a hitch. You have contained the failure.

Retries and Idempotency

Finally, let us talk about the simplest yet trickiest pattern: retrying a failed request. A temporary network blip might cause a request to fail. The obvious fix is to just try again, right? But what happens if the original request did succeed, but the success response got lost on its way back?

If a user clicks "Pay Now" and the request times out, retrying it might charge them a second time. This is where Idempotency becomes your absolute best friend.

An idempotent operation is one that can be performed multiple times but has the same effect as being performed only once. You achieve this by sending a unique "idempotency key" (like a transaction ID) with each request. The receiving service then checks if it has already processed a request with that key. If it has, it does not perform the action again; it just returns the original successful response. This makes retries safe.

Building a solid plan for recovering from these kinds of incidents is crucial, and our own disaster recovery planning checklist is a great place to start.

Advanced Patterns for Data Flow and Consistency

Alright, we have covered how to keep our systems from falling over when things inevitably break. Now, let us wade into some of the more mind bending—but incredibly powerful—patterns. These are the ones that unlock truly sophisticated ways to manage data flow and understand its entire history.

I will be honest, the first time I ran into these, my brain tied itself into a pretzel. But once it clicks, you start seeing the possibilities everywhere.

We are talking about CQRS (Command Query Responsibility Segregation) and Event Sourcing. These two are often used together, and they represent a fundamental shift from how most of us were taught to build applications.

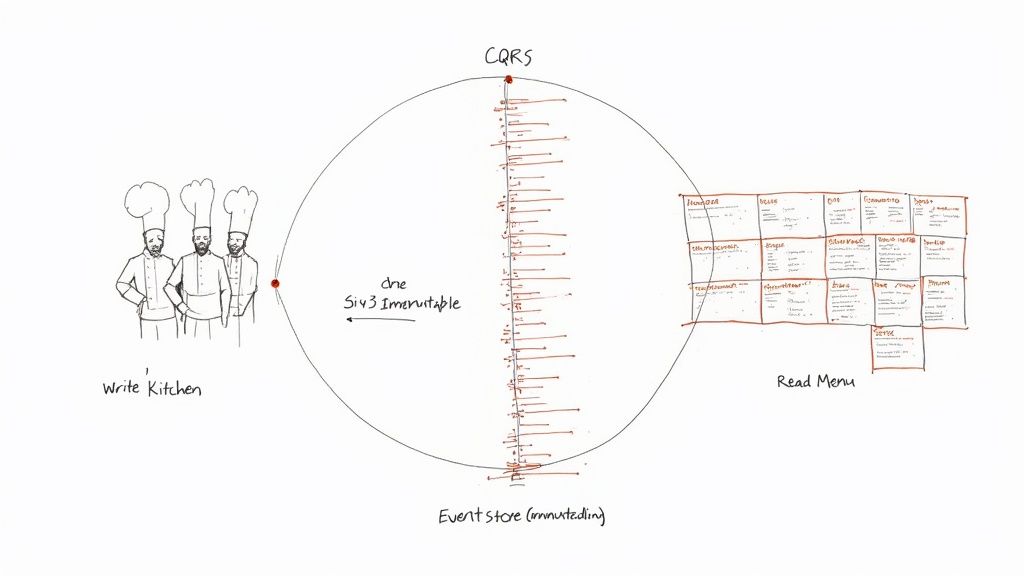

Separating Your Kitchen From Your Menu

Let us kick things off with CQRS. Picture a busy restaurant. You have got two completely different operations going on.

- The Kitchen (Writes): This is the chaotic, state changing hub where orders are taken, ingredients are prepped, and meals are cooked. It is a complex environment optimized for one thing: processing commands like "Make one large pepperoni pizza."

- The Menu (Reads): This is what customers look at. It is a simple, read only view of what is available. It does not need to know the messy details of how the pizza is made, just what is on it and how much it costs.

In a traditional app, the kitchen and the menu are the same entity. We use a single data model to both update information and display it. This works fine for a while, but as the application gets more complex, that single model becomes a bottleneck, getting pulled in two completely different directions.

CQRS just formalizes the restaurant analogy. It tells you to build two separate models:

- The Write Model (The Command side): This is your kitchen. It is built to handle commands that change the system's state. It is all about validation, complex business logic, and ensuring consistency.

- The Read Model (The Query side): This is your menu. It is a highly denormalized, read optimized view of the data. Its only job is to answer questions and display information as fast as humanly possible.

The big idea with CQRS is to stop trying to make a single, one size fits all data model work for everything. By splitting reads from writes, you can optimize each path independently, which can lead to huge wins in performance and scalability.

This separation gives you incredible flexibility. Your write database could be a rock solid SQL server focused on transactions, while your read models might be scattered across Elasticsearch for blazing fast search, Redis for caching, and even a graph database for powering recommendations—each one perfectly suited for its job. Getting these disparate services to talk to each other effectively is where having a solid strategy for seamless API integration becomes critical.

Event Sourcing: The Ultimate Audit Log

So, how do you keep these separate read and write models in sync? This is where Event Sourcing makes its grand entrance. It is a radical and, frankly, brilliant idea.

Instead of storing the current state of your data, you store an immutable sequence of all the state changing events that have ever happened.

Think about a bank ledger. The bank does not just store your current balance. It stores a perfect, unchangeable record of every single deposit and withdrawal. Your balance is just the result of adding and subtracting all those events.

This stream of events becomes the absolute single source of truth.

UserRegistered { userId: "123", name: "Alice" }UserChangedEmail { userId: "123", newEmail: "[email protected]" }ItemAddedToCart { userId: "123", itemId: "abc", quantity: 2 }

To know the current state of a user's account, you simply "replay" these events in order. This simple change in perspective has profound consequences.

The Power Couple: CQRS + Event Sourcing

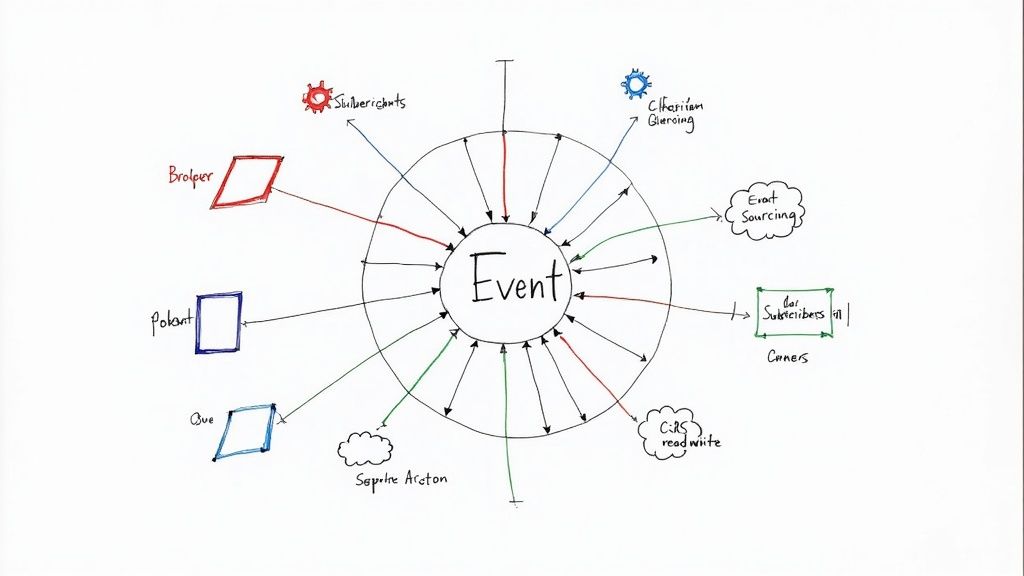

When you combine CQRS with Event Sourcing, something magical happens. The event stream created by your Write Model becomes the perfect fuel for updating all your Read Models. You have separate processes (often called projectors or listeners) that subscribe to this event stream and build whatever read optimized views they need.

This combination is a cornerstone of many modern, highly scalable applications. If this is piquing your interest, you will find that a deeper dive into event driven architecture patterns is a natural next step.

So, why go through all this trouble?

- Auditability & Debugging: You have a perfect, unchangeable log of everything that ever happened. Debugging is no longer about guessing what corrupted your database state; it is about replaying history to see exactly where things went wrong.

- Temporal Queries: You can answer questions about the past that are nearly impossible with traditional models. "What did this user's shopping cart look like at 3:15 PM last Tuesday?" Easy. Just replay events up to that specific point in time.

- Flexibility: Need a completely new way to look at your data for a new feature? No problem. Just build a new Read Model and project the entire history of events into it. You never have to do a painful, risky data migration again.

Of course, this power does not come for free. The biggest tradeoff is complexity. You are now managing at least two data models, the eventual consistency between them, and the infrastructure to handle the event stream. It is definitely not a pattern to reach for on a simple CRUD app.

But for complex business domains where auditability, historical accuracy, and scalability are non negotiable, it is an absolute game changer.

Putting Theory Into Practice With Common Tools

Alright, we have waded through a lot of the "what" and "why" behind distributed systems patterns. It is easy to get lost in the theory, picturing massive, complex architectures run by hundreds of engineers at Google or Netflix.

But what about the rest of us? What does all this mean for a small startup team juggling Python, Django, Celery, and a handful of open source tools?

Let us bring this down to earth. I have seen teams get paralyzed by choice, convinced they need to implement a perfect, textbook version of every pattern from day one. That is a fast track to over engineering and burnout. The truth is, these powerful concepts are surprisingly accessible, and you can start applying them piece by piece with the tools you probably already use.

The key is to solve the problem you have right now, not the one you might have in five years.

A Mini Case Study: Evolving a Feature

Imagine your startup has a feature that generates a custom PDF report for users. In the beginning, it is a simple, synchronous process tucked inside your Django monolith. A user clicks a button, your server crunches some data, builds the PDF, and sends it back. Easy enough.

But as you grow, this becomes a huge bottleneck. Reports start taking 30 seconds to generate, tying up web workers and making the user experience painfully slow. This is your classic first step into distributed thinking.

Step 1: Decoupling with Celery and RabbitMQ

The first move is not to shatter your monolith into a dozen microservices. It is much simpler: make the task asynchronous. You can define a Celery task to handle the report generation.

Now, when a user requests a report, your Django view does not do the heavy lifting. Instead, it just drops a tiny message onto a RabbitMQ queue—like leaving a note for a helper. A separate Celery worker eventually picks up that note, generates the PDF in the background, and emails the user a link when it is done. Just like that, you have implemented a basic Queue Based Load Leveling pattern.

Step 2: Adding Resilience with Redis

Okay, what if generating a specific type of report is flaky? Maybe it depends on a third party API that times out occasionally. You cannot let one bad report crash the whole worker process.

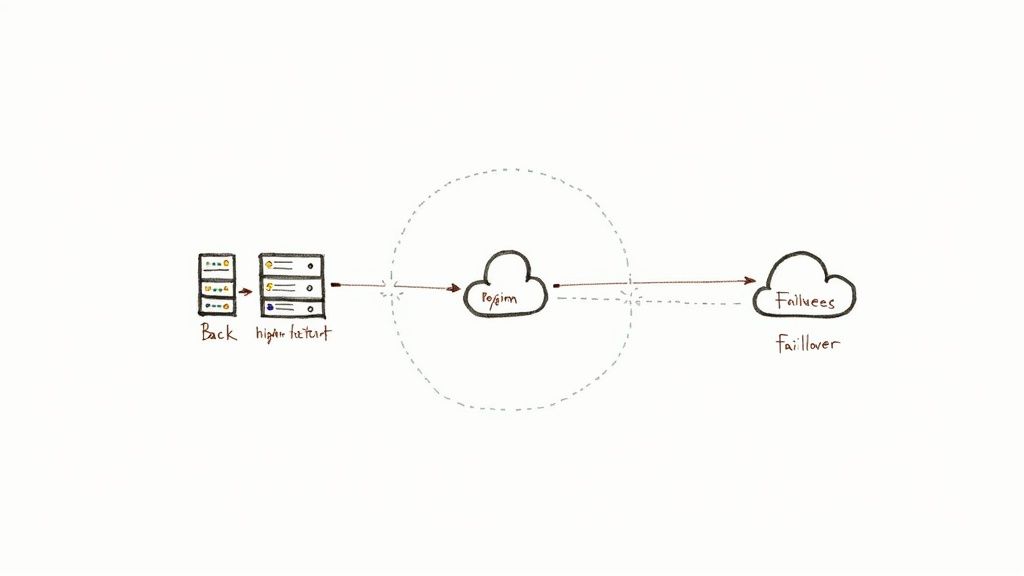

This is a perfect spot to implement a simple Circuit Breaker. You can use a Python library or even just Redis to track failures. Before a worker even tries to generate the report, it checks a counter in Redis. If there have been more than, say, five failures for that report type in the last minute, the breaker "trips." The task is immediately failed and re-queued for later, giving that external API time to recover without bringing your system to its knees.

Step 3: Coordinating with Leader Election

Let us toss in a new requirement: a single, periodic task must run to clean up old reports, but only one worker in your entire Celery cluster should ever run it at a time. If multiple workers ran it simultaneously, you would have chaos—duplicate work, race conditions, you name it.

Here, you can implement Leader Election using Redis. All your workers can try to acquire a distributed lock (which is just a specific key with a short expiration time). Only the single worker that successfully grabs the lock becomes the "leader" for that brief period and runs the cleanup task. It is a simple, effective way to guarantee a singleton process in a distributed world.

You do not need a massive budget or a specialized team to start using distributed systems design patterns. The most powerful tools—Redis for locking, RabbitMQ for queuing, and Celery for execution—are open source and ready to go.

The journey from abstract concepts to working code has become so much clearer over the years. A decade ago, this stuff felt like ad hoc recipes passed around by senior engineers. Now, we have organized catalogs and a shared language for these common problems. To see just how formalized this has become, you can find a comprehensive catalog that lays out dozens of these patterns with their specific trade offs in the Patterns of Distributed Systems.

The big takeaway here is that you can evolve your system gracefully. Start small, identify a real pain point, and apply the simplest pattern that solves it. You can build an incredibly resilient and scalable system one piece at a time.

Hard Won Lessons From the Trenches

Theory and diagrams are clean. Production is messy. After years of building, breaking, and fixing distributed systems, I have learned that the biggest challenges are often not technical, but human and philosophical. Here are the hard won lessons I wish someone had shared with me when I was just starting out.

Do Not Chase Ghosts with Premature Optimization

The number one pitfall I see teams fall into is adopting complex distributed systems design patterns before they have the problems those patterns solve. It is incredibly tempting to build for "web scale" from day one, but this is a classic case of premature optimization.

I once spent weeks implementing a sharding strategy for a service that had fewer than 1,000 active users. The effort was immense, the code became incredibly complex to reason about, and the real world benefit was exactly zero. We burned weeks of runway on a ghost problem.

Remember, every distributed pattern you add introduces new failure modes and a steep tax on cognitive load. Before reaching for sharding or event sourcing, be brutally honest. Do you have a scaling problem right now, or are you just building what you think a "real" tech company should build? Start simple. A well designed monolith can often take you much further than you think.

If You Cannot See It, You Cannot Fix It

A distributed system without robust observability is not a system; it is a black box full of mysteries. When something breaks—and it always will—you will be flying blind.

In a monolith, you have one big haystack to search for a needle. In a distributed system, you have a hundred haystacks, and you are not even sure which one has the needle.

This is why investing in observability from the very beginning is not optional. It is a fundamental requirement for survival. For me, this is the non negotiable baseline:

- Structured Logging: Every single service should emit logs in a consistent, machine readable format like JSON. No exceptions.

- Comprehensive Metrics: You need to track everything. Request latency, error rates, queue depths, database connection pool usage, CPU utilization—if it moves, graph it.

- Distributed Tracing: This is your superpower. The ability to follow a single user request as it hops across multiple services is your single most powerful debugging tool. Without it, you are just guessing.

Your Architecture Shapes Your Team

Finally, never, ever forget the human element. The architectural choices you make have a direct and profound impact on your team's structure, communication patterns, and even their well being. This is the stuff that is often left out of textbooks but is absolutely crucial for real world success.

When you break a monolith into microservices, you are also breaking your team's workflows. Suddenly, deployments need to be coordinated across multiple teams. Cross team communication becomes critical for debugging issues that span service boundaries.

And perhaps most importantly, your on call rotation changes forever. A failure at 3 AM is no longer about restarting a single server; it is a complex investigation across a dozen services owned by different people, trying to piece together a story from scattered logs and metrics. Your architecture dictates how painful that 3 AM call is going to be. Design wisely.

Answering Your Distributed Systems Questions

As engineering teams start digging into these patterns, I have noticed the same questions pop up time and time again. Let us tackle some of the most common ones I hear from folks just getting their feet wet with distributed systems.

When Should I Start Using These Patterns?

Honestly? You should only start reaching for these patterns when the pain of your monolith becomes impossible to ignore. Not a second sooner.

The classic signs are performance bottlenecks you cannot solve by just throwing more hardware at the problem (scaling up), or when your development teams are grinding to a halt, constantly tripping over each other with merge conflicts. Adopting these patterns too early is a textbook case of over engineering. You will introduce a mountain of complexity for zero real world benefit.

Which Pattern Is Most Important to Learn First?

For almost every team, Replication is the first and most critical pattern to get right. It is the bedrock. It directly solves the most fundamental problems: high availability and making sure you do not lose data.

By making redundant copies of your services and data, you immediately build a foundation of resilience. You move away from having a single point of failure that can take your entire system down. It is the most practical and impactful first step you can take.

Can I Mix and Match Different Patterns?

Absolutely. In fact, you pretty much have to. Real world systems are never built using just one of these patterns in isolation.

A very common setup is to use Sharding to partition data for massive scale, then apply Replication within each shard to ensure it is highly available. Then, you wrap the microservices that talk to those shards with Circuit Breakers to handle failures gracefully. The real art is in picking the right cocktail of patterns to solve the specific scaling and reliability challenges you are facing.

What Is the Biggest Mistake Teams Make?

The single biggest, most catastrophic mistake I see is underestimating the importance of observability.

A distributed system without comprehensive logging, metrics, and distributed tracing is a complete black box. When—not if—something fails, you will be flying blind with no idea where the problem is or what caused it.

Investing in your observability stack from day one is not a "nice to have." It is a non negotiable, foundational requirement for operating and debugging these systems successfully. You absolutely must be able to see inside the machine.

Are you an early stage startup hitting a scaling wall or looking to build a robust, production grade system with Django, Celery, or GenAI? As an engineering consultant, I help teams like yours accelerate their roadmap and build resilient architectures. Let's talk about how Kuldeep Pisda can strengthen your technical foundations. Learn more and get in touch.

Become a subscriber receive the latest updates in your inbox.

Member discussion